Invasion of the Brain-Shrinkers

I have Terry Frost from the YouTube channel “Terry Talks Movies” to thank for pointing me to a series of radio dramas and postwar B-movies which I had hypothesized as a possible source for one of Fleming’s books, if in fact they even existed.

As I leafed through Moonraker for the very first time a year or two back, I was struck by how much the opening chapters reminded me of the structure of an old radio play. We have the equivalent of brisk narration peppered with impatient snatches of dialog, weaving together story elements at breakneck speed lest the audience feel tempted to fiddle with the dial and look for alternate sources of entertainment.

It reminded me of a critic’s assessment of the Bond canon many years ago, as being made out of old movie serials and Jules Verne novels. Moonraker does feel like a book that has been adapted from another medium.

However, I had never before heard of Special Agent Dick Barton until Terry Frost brought me up to speed.

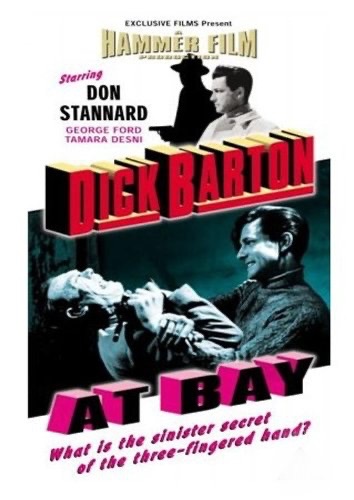

In 1946 Dick Barton took his first bow on BBC Radio, before graduating to a trio of low-budget Hammer films and a much later TV series. In his early adventures Barton usually had to thwart the schemes of unrepentant Nazis bent on settling the score over their recent shellacking in World War II. The peril devised for the first film, Dick Barton: Special Agent, is an especially deadly bacillus being smuggled into England to contaminate drinking water.

For the final Barton film produced by Hammer, Dick Barton Strikes Back, the hero must stop a mad scientist’s scheme to use Blackpool Tower to broadcast a signal from his fiendish brain-shriveling death ray.

If the plot sounds more like a Bond parody than a Bond prototype, Fleming nonetheless may have had the adventures of Dick Barton in the back of his mind as he prepared his third thriller, Moonraker.

This is the Fleming novel in which 007 isn’t dispatched to an exotic locale, almost as if he’s forced to battle evil forces on a budget. The threat is strictly local this time, London being ground-zero for Sir Hugo Drax’s warhead, while most of the action takes place in Fleming’s beloved countryside of Kent. Drax is, of course, secretly a German seeking revenge for the war in which his country had been humbled and he had been disfigured

Judging from his scattershot approach, Fleming appeared to have no idea where the Bond series was headed or what his hopes for it were. He just seemed to be trying everything he could think of. His first novel had been turned into a disappointing live drama for American television. Attempting to adapt Live and Let Die for a screen of any size would have been courting trouble in the 1950’s.

Moonraker, on the other had, has the feel of a serialized drama for radio or, perhaps even television. There is nothing extravagant about it that requires more than some mocked-up control panels and a few papier-mâché boulders, for those cliff-hanger moments which involve some actual cliffs.

Fleming had not yet found his footing or his muse. After one more futile attempt to crack the American market, he would finally begin to make his mark by literally writing fairy tales for adults.

Following up with Disney adventure fare, he would next branch out to entertain his growing legion of readers with updated versions of more obscure classics, which thus far had been relegated to musty academia. That is, until Ian Fleming asked himself, “Green Knight, eh? I wonder how James Bond would handle him?”