Twice, for Good Measure

Imagine Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli, armed with a recent option on Fleming’s novels, sorting through their new property and wondering where to start.

Having just been published, Thunderball was not yet recognized as a course-change, but only another volume in a remarkably eclectic series of adventure stories. Viewing Fleming’s entire output today we can see the novels falling into three distinct groups.

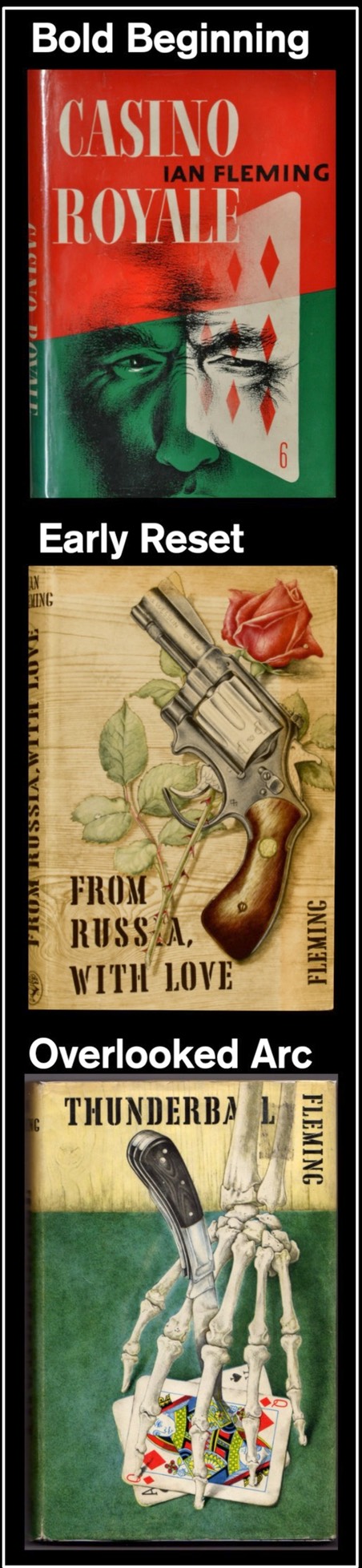

After Casino Royale, a promising freshman effort (which had been sold to a different film producer), the next few books are evidence of a novice writer struggling to find a solid footing while appealing to a broader audience on both sides of the Atlantic. As Fleming’s mentor Raymond Chandler pointed out, while not terrible, each successive work from this early period, Live and Let Die, Moonraker, and Diamonds Are Forever, was slightly less interesting than the last.

After apparently choosing Walt Disney as his guiding star, Fleming began crafting his masterpiece, From Russia With Love. An ingenious mashup of Disney’s Cinderella and the studio’s forthcoming Sleeping Beauty, FRWL lifts the basic story from the unreleased second Disney film, but seasons it with memorable characters from the first, amusingly weaving these borrowed elements into the framework of a classic spy thriller.

A reinvigorated Fleming slightly modified the process with Doctor No, relocating Disney’s 20,000 Leagues to a mysterious island in the Caribbean, while dropping in the otherworldly jungle waif from W. H. Hudson’s Green Mansions to create a spooky love interest for his hero.

Although no prior Disney films seem to provide source material for Goldfinger, the book still fits squarely into Fleming’s playful middle period, with story elements apparently spun from equal parts of “Rumpelstiltskin,” and “The Emperor’s New Clothes.”

The book is also at least Disney-adjacent, published the same year the Disney studio released Darby O’Gill and the Little People, a project which Walt Disney had been teasing since the early 50’s.

Fleming could be acknowledging his recent debt to Disney when Bond playfully asks the five-foot-tall Auric Goldfinger, “What are we going to do, rob the end of the rainbow?” In a similar vein, after Goldfinger conducts a seminar for his prospective criminal confederates, Miss Pussy Galore asks no one in particular, “What was the name of that fairy tale?” The one she’s thinking of is, of course, “Sleeping Beauty,”

Despairing of ever finding a suitable plot to rival the one he had crafted for Goldfinger, Fleming mused about confining Bond to short stories such as those comprising his follow-up volume, For Your Eyes Only. When his publisher insisted on another novel, the writer began to flesh out the screenplay from an abandoned film project sometimes called Longitude 78 West.

The resulting book, Thunderball, which adopts a far more serious tone than the film with the same name, would mark the start of a five-volume character-arc for James Bond. Dipping into Greek mythology and Middle English poetry, but always with one eye on popular culture, Fleming would drag his hero through Hell and back in subsequent books, and then across a finish line of sorts, while making sure to leave Bond safely teed up for a fresh start.

Fleming’s Thunderball owes a debt to doomsday literature from the dawn of the nuclear age - think Neville Shute’s On the Beach with the title character from Jean Anouihl’s Antigone. Make no mistake, Bond is hardly the hero of Fleming’s story. His most important job is to be a careful listener as Domino Vitale recites her family history, after which he must unleash a vengeful tigress on Emilio Largo, heir-apparent to Ernst Stavro Blofeld.

Fleming may be signaling a re-invention of the Bond series, or at least a fork in the road, by creating a mirror-image of Casino Royale. This time around it is the innocent girl who is subjected to merciless torture of her tender flesh, and Bond who spirals into a deep funk of guilt and regret. Unlike Vesper, Bond does not take his own life, though in order to make a full recovery a few books on, he will have to die and be reborn.

Thunderball, The Spy Who Loved Me, and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service show Bond digging an ever-deeper pit for himself until finally beginning the long climb toward daylight in You Only Live Twice. However, he will only achieve full redemption after squaring off against Francisco Scaramanga in The Man With the Golden Gun, while respecting all of the basic tenets of chivalrous conduct.

The Eon team’s plan to adapt Thunderball for their first Bond film might strike us today as a symptom of insanity or the hubris of ignorance. Trying to tackle an expensive logistical nightmare right out of the starting gate could have ended the series before it began. Thunderball must have appealed to Broccoli and Saltzman not only because the book was hot off the presses, but because it tackled the trendy concern of nuclear proliferation.

Learning that the film rights to Thunderball were in dispute, the producers wisely picked Dr. No to get their feet wet, following up with the remaining titles from Fleming’s middle period, From Russia With Love and Goldfinger. These choices represented Fleming hitting his stride, before embarking on his bold venture into a multi-part saga of tragedy and redemption.

The team’s first three cinematic adaptations seemed to set the standard for what audiences would come to expect from a Bond film: an outrageous plot devised by a colorful villain, scenic locales, a parade of beautiful women, and a hero grittily willing to wage war against Her Majesty’s enemies, so long as he’s permitted a few hedonistic perks along the way.

The liberties that were taken while adapting Fleming’s tales for the screen, and why the changes seemed necessary at the time, might deserve a closer look.