Sigmund Freud has tea with the Brothers Grimm

You’ve heard of the elevator pitch, a story-idea boiled down to its essence. By the time the elevator doors open a busy Hollywood executive has digested the pitch and made up his mind, yea or nay.

"It’s like Robinson Crusoe, but he’s stranded on Mars."

"This diplomat adopts a kid who turns out to be the Antichrist."

"A greedy little gnome recruits a gang of perverts to rob Fort Knox."

That last one could have been the elevator pitch in Ian Fleming’s mind when he dreamed up one of the most celebrated and certainly the most outlandish entry in his James Bond series. In Goldfinger, a thriller with multiple allusions to fairy tales, Fleming’s chief innovation may have been introducing the Brothers Grimm to Sigmund Freud.

The names of most of Goldfinger’s associates suggest that there is something at least off-center about their sexuality, e.g., "The Cement Mixers," Odd Job, Billy “The Grinner” Ring, Jack Strap, Mr. Solo, Pussy Galore. On the other hand, modern ethnographers assure us that “Rumpelstiltskin” was thrumming with sexual undercurrents long before Fleming put his signature spin on it.

Traditional roles in the familiar tale of the gold-spinning imp have been subdivided or fused together to add complexity to the storyline and to keep us guessing about what insane twist inevitably awaits us around the next corner.

Auric Goldfinger seems to be a composite of several fairy-tale characters besides the opportunistic Rumpelstiltskin. He’s also the greedy king from the same story who always wants more, a Pied Piper cheerfully leading his followers over a cliff, and the proud Emperor who elicits flattery despite the naked absurdity of his scheme, lest more naysayers wind up at the bottom of a stairwell with the late Mr. Springer.

Instead of one miller’s daughter we get two Masterton girls, Jill and Tilly, two sides of a coin differentiated chiefly by sexual orientation. Bond has a fleeting, athletic fling with the lusty Jill, but gets the cold shoulder from Tilly, a prim outdoorswoman. When both women cash out early, there’s only one other, seemingly unlikely candidate who hangs around long enough to share Bond’s bed at the fadeout.

Even some of Fleming’s ardent fans took issue with Pussy’s sudden “conversion” in the final chapter. She explains to Bond that her recent preference for women stems from childhood trauma suffered at the hands of a relentless uncle. Given Pussy’s Southern background and her resemblance to Elizabeth Taylor, there’s a good chance that Fleming was having some fun at the expense of playwright Tennessee Williams.

Just as Fleming prepared to write the first draft of his story, Williams’ psychodrama Suddenly Last Summer debuted off Broadway, while Miss Taylor prepared to tackle the role of the sex-starved Maggie the Cat in the film version of Cat On a Hot Tin Roof. After completing the shoot she would be cast in the movie adaptation of Suddenly Last Summer, playing a young woman facing a lobotomy intended to bottle up the ugly family secrets she’s privy to, secrets involving homosexuality, incest, pederasty, and cannibalism.

By the late 1950’s audiences and readers couldn’t help becoming acquainted with Freudian themes, or at least their pop-culture manifestations. Robert Bloch’s Psycho was written the same year as Goldfinger. I was also the year Joanne Woodward gave an Oscar-winning performance in Three Faces of Eve. Tennessee Williams’ Southern-marinated Freud was already being served up on stage and screen, with additional courses waiting in the wings.

When Hitchcock’s film of Psycho came out the following year, in addition to seeing the apparent protagonist killed off before halftime, moviegoers’ sensibilities were assaulted by their first-ever closeup shot of a toilet. Fleming had already carried the ball further, making the raising of a toilet seat a significant plot point in Goldfinger, his absurd fairy tale about traditional masculinity winning the day.

What about the film?

Like the casting of an imposing Gert Frobe as the five-foot-tall red-haired imp of the novel, most of the changes made to Fleming’s tale do no serious harm and probably improve the film.

Watching James Bond strangle a tiny man to death with his bare hands would have made moviegoers squirm. Yes, assembling the gangsters and explaining the scheme to them in great detail only to kill them off moments later, makes no sense. However, sending Mr. Solo away to be shot and crushed shortly after gassing the others, does emphasize the notion that anything can happen at any moment.

Shifting the master plan from stealing the gold to making it radioactive not only adds credibility to the plot, it changes Mr. Goldfinger from being a mere thief to a soiler.

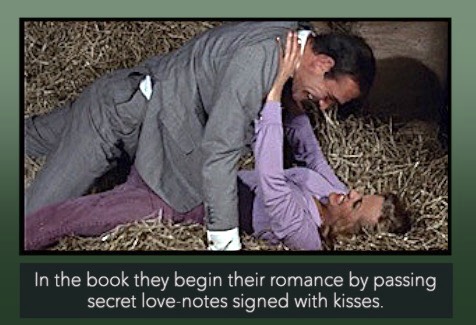

I won’t even quibble with the scene in the stable where Bond forcibly kisses Miss Galore (anyway a kiss is all we see). It fits in well with Fleming’s fairy-tale motif as a time-tested remedy for breaking a magic spell. Unfortunately it only set a low bar for Bond's conduct in the movies, which swiftly grew worse.