Cinderella, as Fleming Saw It

Walt Disney’s Cinderella was the fifth highest-grossing film to play in British cinemas in 1950. As the company readied its latest and even more lavishly-mounted fairy tale, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella was re-released to theaters in 1957, the year Fleming published From Russia, With Love.

The opening paragraphs of the novel, a description of Red Grant as the apocalyptic Great Red Dragon of the Book of Revelation, attended by a woman clothed with the sun, is a prime example of Fleming’s art: adapting a familiar artifact, and imaginatively weaving it into the fabric of a James Bond thriller. It’s exactly what he did with Disney’s Cinderella.

Fleming does everything short of formally announcing that Ali Kerim Bey or “Darko” will essay the role of Bruno the faithful bloodhound from Cinderella, while Krilencu will fill in for the sly Lucifer, Lady Tremaine’s spoiled cat. Flushed out of an upper-story window by an enemy, both Krilencu and Lucifer will exit the story after dropping to a cobbled street. Krilencu’s fate is sealed with a bullet, while Lucifer’s demise is merely assumed. He may have returned for a sequel.

Just In case we fail to see the connection between Lucifer and Krilencu, prior to the attack by Krilencu’s Bulgars on the gypsy camp, a black cat with green eyes sits among the gypsy children and begins licking his chest. There had been a similar underlining of Grant as a dragon in the first chapter, when a dragonfly investigates Grant’s massive, motionless body before sensing signs of life and flitting away.

The mice in Cinderella have an intricate network of passageways and apertures for keeping track of the cunning Lucifer and Cinderella’s scheming stepmother. Bond’s friend Ali Kerim Bey traverses a tunnel under the local Russian HQ, where a navy-surplus periscope peers through what “Darko" refers to as “a small mouse-hole” carved into the corner moulding.

To be certain we notice, Kerim underlines the homage to Disney by remarking, “Once when I came to have a look, the first thing I saw was a big mousetrap with a piece of cheese on it.”

“The perfect touch,” Lady Tremain remarks, before provoking her daughters into shredding Cinderella’s gown.

Moments after placing her hand on the Tatiana's knee, Klebb purrs, “A real labor of love."

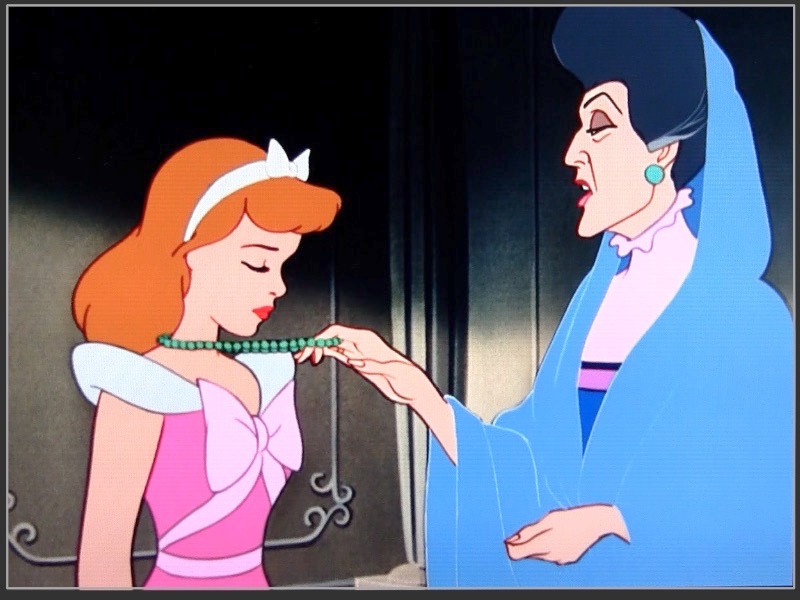

Reading Fleming’s take on a familiar fairy tale can also give us disturbing insights into the Disney version. Rosa Klebb, playing the role of Cinderella’s domineering stepmother in Fleming’s tale, is not only jealous of Tatiana Romanova, but has amorous designs on the girl (only rather creepily implied in the film, as seen above).

The French version of the fairy tale used by Disney and Fleming is called “The Tale of Little Brier-Rose.” Klebb is German for “sticky” making Rosa Klebb “Sticky Rose,” suggesting that in her mind at least, she should be the heroine of the story. What better way to get even with her replacement than by possessing the girl before sending her off to die on the Orient Express?

Readers who make the connection between Fleming’s book and Disney’s Cinderella will never be able to watch the various shades of sadistic delight crossing Lady Tremaine’s face without wondering what the animators were thinking. We can at least be sure what Fleming assumed they were thinking.