Disney and Fleming Tackle Jules Verne

Walt Disney and Ian Fleming were born in the first decade of the 20th century and died in the mid 1960’s, their creative streaks snuffed out early by cigarettes, combined, at least in Fleming’s case, with a habit of consuming immoderate amounts of vodka. Both men left lasting marks on popular entertainment. One of them may have left fingerprints on a few of the other man’s projects. At the very least, their sensibilities seemed to be in sync, right down to what they looked for in a leading man.

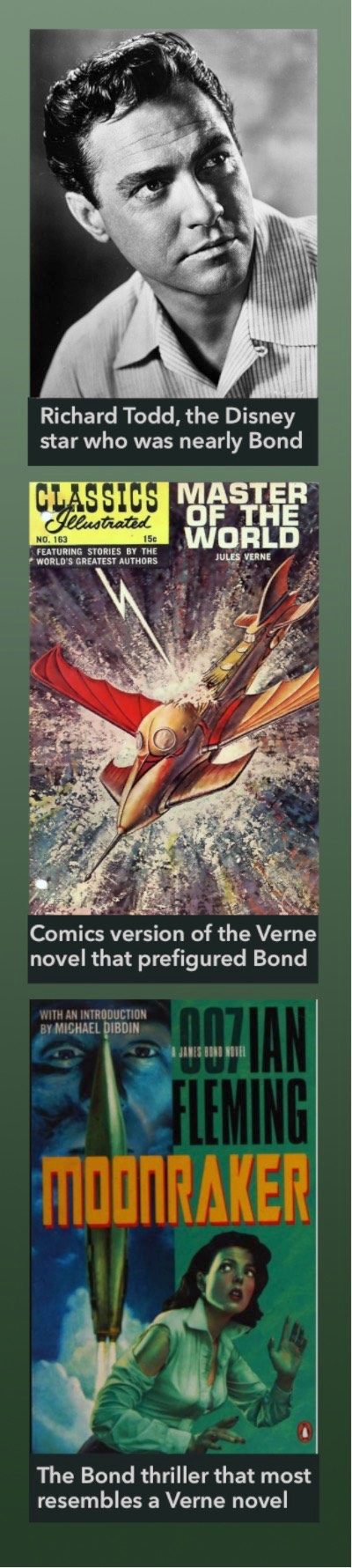

One of Fleming’s early picks to play James Bond, Richard Todd, appeared in three Disney movies in the early 1950’s. The chap who eventually got the gig, Sean Connery, caught the eye of Mrs. Albert Broccoli when she saw him in Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People. A strong contender who would turn down the chance to play Bond, Patrick McGoohan, was immediately snapped up by Disney to fill the void left by Todd and Connery.

From Russia With Love, Fleming’s effort to strive for “a little higher grade” of espionage potboiler, takes its subtext from the same French version of “Sleeping Beauty” that is the source of Disney’s animated film. Although the Disney version landed in theaters in 1959, two years after Fleming’s book was published, the studio had been toiling on the project since 1952, and their work was not conducted in secret. A similar situation resulted when MGM’s long struggle to adapt W. H. Hudson’s Green Mansions for the screen allowed Fleming to get his version of Rima the Bird Girl, Honeychile Rider, into bookstores a year before the film opened. (Although it’s hard to imagine Mansions star Audrey Hepburn as a Bond girl, she would later pair up with Sean Connery for Robin and Marian, and their chemistry is undeniable.)

According to a recent biographer, Fleming grew up devouring the works of Jules Verne, leading to speculation that Fleming’s diabolical masterminds were natural offshoots of Verne’s Nemo and Robur, who, like Blofeld, showed up for sequels. Robur, the mad inventor in Robur the Conqueror as well as Verne’s swan song, Master of the World, seems to prefigure the classic Bond villain when, instead of Verne’s usual motley assortment of castaways, he squares off against federal investigator John Strock, an agent who tries to infiltrate the inventor’s volcanic lair and is later taken prisoner.

If Fleming ever wrote a novel that paid tribute to his boyhood infatuation with Verne, it was probably Moonraker, the story of sinister industrialist Hugo Drax, whose name even sounds like a Verne villain. By the time Fleming came up to cruising speed with Dr. No, Jules Verne was just one more ingredient to be mixed into a tasty ragout that included Fu Manchu, H. Rider Haggard, naturalist W. H. Hudson, assorted Greek myths, and Walt Disney.

What Fleming seemed to draw from 20,000 Leagues for Dr. No, isn’t so much the flavor of Verne, but Verne as distilled through Walt Disney. Disney's screenwriters discovered early on that there’s no plot to speak of in 20,000 Leagues. The novel is a longer version of the now-defunct ride at Disneyland, a goggle-eyed voyage spent peering at wonders of the deep. Verne ends his book by arranging for the Nautilus to be caught in a whirlpool, giving Nemo’s guests an opportunity to jump ship. The Disney team's decision to make the whole yarn the story of a jail-break on a submarine, invests the movie with much-needed dramatic tension.

When James Bond tumbles out of Dr. No’s gauntlet and jabs a blade into his captor's monstrous squid, Fleming probably isn’t just tipping his hat to Verne, but to the Disney artists who wisely made the squid-attack the unforgettable climax of their film. The scene was considered so crucial to the movie’s success that the studio expensively reshot the entire sequence.

While EON couldn’t afford any sort of squid for Sean Connery to battle in 1962, they did borrow the climax from the 1954 Disney film, having Bond and Honey make their escape by boat as Dr. No’s reactor blows sky-high. Later Bond movies seemed to mine Verne’s futuristic visions from Master of the World, with its automobile that can drive into rivers and submerge, or take wing and fly over Niagara Falls. By that time, of course, there were already prototypes for real vehicles that could do such things. The flying car was still a daydream when Fleming wrote Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, his book for children.

According to biographer Andrew Lycett, Fleming was aware that a scene in which his flying car circles a church spire resembles one in Disney’s Absent-Minded Professor. Although Lycett seems to imply that Fleming considered taking legal action, since the Disney film was released months before Fleming’s book was published, inspiration either flowed from silver screen to golden typewriter, or else the matter was a genuine and harmless coincidence. Ironically, since EON turned Chitty Chitty Bang Bang into a screen musical in 1968, generations of children have grown up remembering it fondly... as a Disney film.

The confusion is understandable, given the fact that Chitty employed Disney’s go-to tunesmiths the Sherman brothers, as well as Mary Poppins co-star Dick Van Dyke. Regular members of the Bond production crew, John Stears, Ken Adam and Peter Hunt were on hand for the musical, which was co-written by Fleming’s friend Roald Dahl, who had penned the script for You Only Live Twice, but had also worked on a project at Disney during the war. With a cast that includes Desmon Llewelyn and Gert Frobe, it’s no wonder the film feels like a Fleming book that has been turned into a Disney movie. In that respect, it very much resembles Dr. No.

Fleming usually acknowledged his debts, and inserted a few straightforward references to Disney in his later books. The French origin of the mogul’s surname is explored in OHMSS, while Blofeld’s desire to construct a “Disneyland of death” in YOLT makes the versatile villain, amusingly enough, a sort of anti-Disney, presiding over the most magically miserable place on earth.