Firing on All Cylinders

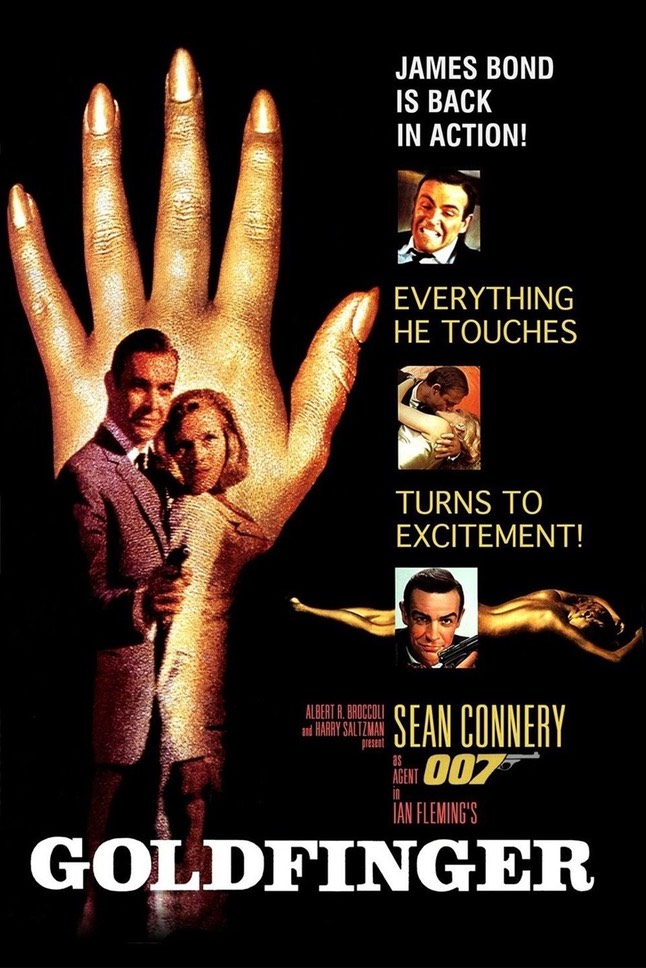

If we think of Dr. No as a run-through for a Bond film and From Russia With Love as a dress rehearsal, then Goldfinger was the big glitzy premiere with searchlights, showers of confetti and a brass band. Blessed with the budget of the two previous films combined, the production wasted nary a penny.

Although it’s the one entry in the series against which all subsequent Bond films would be measured, it was also the first one to give Fleming’s villain and the fiendish plot a major overhaul.

Having resided in the English countryside for decades, Fleming’s Auric Goldfinger seems the model of a prosperous British businessman, albeit a very short one, standing not a hair over five feet tall. Goldfinger’s height lifts him above the dwarfism spectrum by a whole two inches, nudging him into a category which the Brothers Grimm labeled manikin, or “little man.”

By casting a tall, burly German actor in the role and sending a laser beam inching between Bond’s legs instead of a buzzsaw, the film veers away from the book’s fairytale imagery of the diminutive Rumpelstiltskin and his ominous spinning wheel.

Also missing is the book’s catalog of Freudian labels worn by many of the characters Bond meets.

Goldfinger’s gangland confederates, given names in the book which suggest psychosexual abnormalities, are not only minimized in the film but quickly killed off, have been rendered completely unnecessary. There has been a change of plan.

The Auric Goldfinger of the movie is no longer a thief, but a soiler. He hopes to irradiate America’s gold supply to make his own holdings more valuable. Screenwriters Richard Maibaum and Paul Dehn were convinced they had spotted a fatal flaw in Goldfinger’s original scheme: removing the gold from Fort Knox would take too much time, require too many trucks and far too many minions.

All true, perhaps, but entirely beside the point for Fleming. In the book, Goldfinger is no genius with a foolproof scheme. He’s a bullshit artist who ensnares greedy associates in his web of golden dreams. However, the changes wrought by Maibaum and Dehn not only streamline the plot but render it more cinematic, with lasers, gun battles, a cathedral bulging with bullion, and a ticking A-bomb. The book is a splendid page-turner, but the movie crackles with excitement and hilarious surprises.

The idea that anything can happen at any time in Goldfinger keeps the audience giddily off-balance. Why does Goldfinger gas the crooks after explaining his plan to them? Why not? Was he ever not going to gas them? Who cares? Why is solo killed and then crushed inside the car? Showmanship.

In keeping with the previous two entries, Bond is once again far less chivalrous in the film version. He notoriously forces himself on Pussy Galore as they lie on a bed of straw, although since he’s trying to set her free from Goldfinger’s golden spell, her sudden change of allegiance might not be the most illogical thing that happens in the film.

In the book, it’s Jill’s sister Tilly who is the icy lesbian, while Pussy Galore was a victim of childhood trauma. If Bond does indeed help Pussy overcome her fear of men in Fleming’s version, it’s by being kind and patient, not by jumping her in a stable. The pair exchange furtive love-notes on Goldfinger’s plane, messages signed with hearts and kisses, then enjoy a brief tryst before she’s trotted off to jail.

The movie resembles nothing else quite so much as a filmed comic book adaptation of Fleming’s thriller, one intended for grownups, but suitable for all ages. Rough bits are smoothed over, sex is implied, bare skin is tastefully arranged, minor roles are eliminated or merged, and the plot is stripped down and supercharged.

The two previous Bond movies now seemed to be mere appetizers, and stomachs were growling for the main course. When Goldfinger was released, movie theaters in some American cities remained open around the clock to satisfy demand. By the time prints were finally bicycled to screens in rural areas, the premiere of the next Bond film was less than six months away.

A tidal wave of Bondmania was gaining steam.