The Matter of Succession

In a recent post I took an inventory of the men who’ve been cast as James Bond thus far in the seemingly-inexhaustible film series. This was a cursory summation at best. I did not refresh my memory by rewatching everything, or by catching up with some entries for the very first time on streaming services. Rather, it is my recollection of how the various entrants struck me at the time while sitting in a theater seat with an inexpensive box of popcorn cradled in my arm.

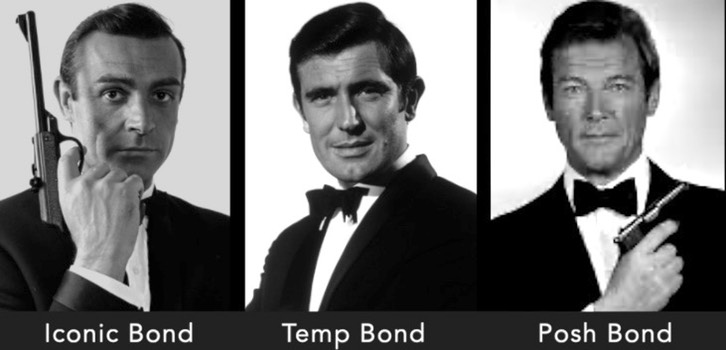

Back when moviegoing was still cheap entertainment I watched most of the Connery series, starting with Goldfinger, sometimes, several times each. After a delay of almost a full decade I finally got a look at the first two entries in the series at a drive-in, a few months before the premiere of Diamonds Are Forever. Thus, while some segment of the population considered Sean Connery irreplaceable, I had only seen him in three Bond films before George Lazenby stepped in.

In fact, the Bond movie which garnered the most repeat viewings from me upon its initial release was On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the one which had also been buffed to highest sheen of technical accomplishment thus far. What’s clear in retrospect is that the company should have used the previous star’s departure as an opportunity to reboot. Instead they seemed bent on trying to gaslight the audience.

A model whose specialty had been dressing as James Bond for a series of commercials, and who only turned 30 after filming wrapped, George Lazenby shows promise in O.H.M.S.S. He is entirely believable as a raw recruit being handed his first assignment, but perhaps not as a living legend in the spy trade.

“This never happened to the other fella,” Lazenby laments during the pre-title sequence. The title montage includes snippets from earlier entries in the series. During playful office banter with the new 007, Moneypenny squeals, “Same old James - only more so!” Bond daydreams at his desk while rummaging through souvenirs of past missions as the soundtrack plays familiar John Barry cues from previous films.

It’s as if the filmmakers decided to force the audience to watch a heavy-handed treatise on the concept of recasting a part, before the movie quite gets going.

Lazenby isn't terrible in the part. He’s just a freshly-minted novice who’s trying to avoid tripping over the cables. In that respect he’s a bit like the Connery of 1958’s Another Time, Another Place. Appearing as Lana Turner’s doomed love-interest, the freshman leading-man had been given pages of lines to recite but no real character to play. By rights the role should have gone to Roger Moore.

My favorite anecdote concerning O.H.M.S.S. is the one where Harry Saltzman asks an attendee at a press screening, “So what do you think of my new monster?”

“You screwed up, Harry,” the man replied. "You should have killed him and kept her.”

Any story concerning Lazenby’s departure should be taken with a grain of salt. The version which has Lazenby being pressured by his agent to turn down a lucrative multi-picture contract to keep playing Bond, in favor of making trippy counterculture flicks on shoestring budgets, may have been an invention designed to save face all around. The fact is that replacing Connery had turned out to be harder than expected. So producers lured him back with an unprecedented payday.

Connery’s most prestigious motion picture credit before Dr. No had been the young male lead in Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People, on the heels of playing loutish, oversexed villains in Action of the Tiger and Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure.

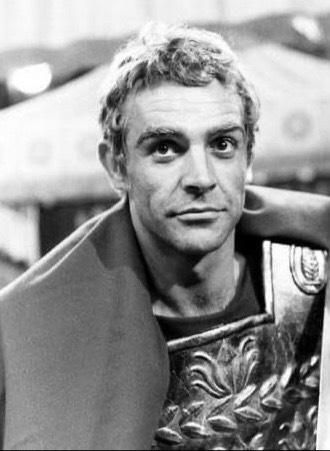

Watching a vintage recording of Connery as Alexander the Great in Terence Rattigan’s Adventure Story, a televised drama from 1961, gives us a glimpse of an actor clearly on the brink of stardom and looking for new worlds to conquer. He played Rattigan’s Alexander, Tolstoy’s Count Vronsky and Sharkespeare’s Macbeth within a matter of months, one year after winning the standout role of Harry Hotspur in the BBC’s An Age of Kings.

When Connery could not be convinced to stick around for a follow-uo to Diamonds Are Forever, producers decided to seek another actor with a proven track record.

After three years at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where he perfected a Mid-Atlantic accent and the art of raising either of his eyebrows or both at once, Roger Moore had gradually built up a resume of supporting roles and third-billed leads on television and in films. His career received a major boost in 1958 when he was cast in the title role of the TV series Ivanhoe, which was followed by steady work in Warner Brothers Westerns, including a short stint as Beau Maverick.

Moore scored the part of Simon Templar in the lead-up to the long-running TV series The Saint in 1962, the same year Connery starred in Dr. No. After The Saint left the airwaves in 1969 Moore teamed up with Tony Curtis as a mismatched pair of do-gooders in The Persuaders, a series which ended its short run just in time to free up Moore for Live and Let Die in 1972.

I had seen Moore as Beau Maverick, as Simon Templar, and as Tony Curtis’s urbane partner, and wasn’t looking forward to his impersonation of James Bond. I needn't have worried. If Moore could be guaranteed to turn every role he played into some slight variation on the suave, earnest, imperturbable gentleman he had perfected over a decade of mostly forgettable films, at the very least he was an actor who seemed to know what he was doing.

There was also the propulsive energy of Paul McCartney’s title song and George Martin’s accompanying score to smooth over the rough patches. Besides, Bond films had become a phenomenon less concerned with fantastical schemes to be foiled ingeniously, than with a series of zany chases punctuated by one-liners and perfectly-timed pyrotechnics.

The Man With the Golden Gun was another matter. Fleming’s book is barely an outline, a means of settling up accounts and putting Bond back into play without the weight of emotional baggage from past transgressions.

Today it’s difficult to remember what the film version is even supposed to be about. There is talk of an energy crisis and some sort of solar-powered contraption. A bounty is placed on James Bond’s head. That amusing Southern sheriff from the previous Moore film pops up for laughs. Somewhere in the proceedings a car executes a midair corkscrew maneuver accompanied by a slide-whistle sound effect, while moviegoers groan. We see a man, or perhaps two men, sporting an extra nipple each, and a gentlemanly duel gets underway on a beach. Then, for some reason, everything starts to explode while Bond dashes about with a bikini-clad girl.

The audience in my theater began trudging up the aisle before the end credits rolled and I was tempted to join them. I have seen the movie exactly once.

It had been ten years since Goldfinger took the world by storm and now the last of Fleming’s Bond thrillers had finally been committed to film, in some form or other. Somehow, it did not seem to be a milestone worth celebrating.