Across the Zeitgeist

James Bond may have sprung to life with the publication of Casino Royale, but he came of age in From Russia, With Love when Ian Fleming followed his mentor’s advice and decided "to aim for a little higher grade."

As the book began to catch fire with the reading public there was renewed talk of adapting the Bond thrillers for films, perhaps re-teaming Cary Grant and Grace Kelly, stars of Hitchcock’s To Catch A Thief, for the roles of Bond and Tatiana Romanova. While it may have been only a trial balloon launched by a publicist, someone suggested offering Hitchcock the director’s chair. It seemed right up his alley.

It did indeed, since the book features a mysterious blonde at the beck and call of diabolical forces, with James Bond filling in for Hitchcock’s naive protagonist, and a splendid MacGuffin in the Spektor decoding device. It turns out that the great director was interested, but only in making his own version of the story, a screenplay crafted by Ernest Lehman called North By Northwest.

Four years later EON turned the tables when they finally filmed From Russia With Love, by having an enemy helicopter swoop down on Bond as he runs for cover, an obvious callback to the crop duster which suddenly changes course to buzz Cary Grant in North by Northwest.

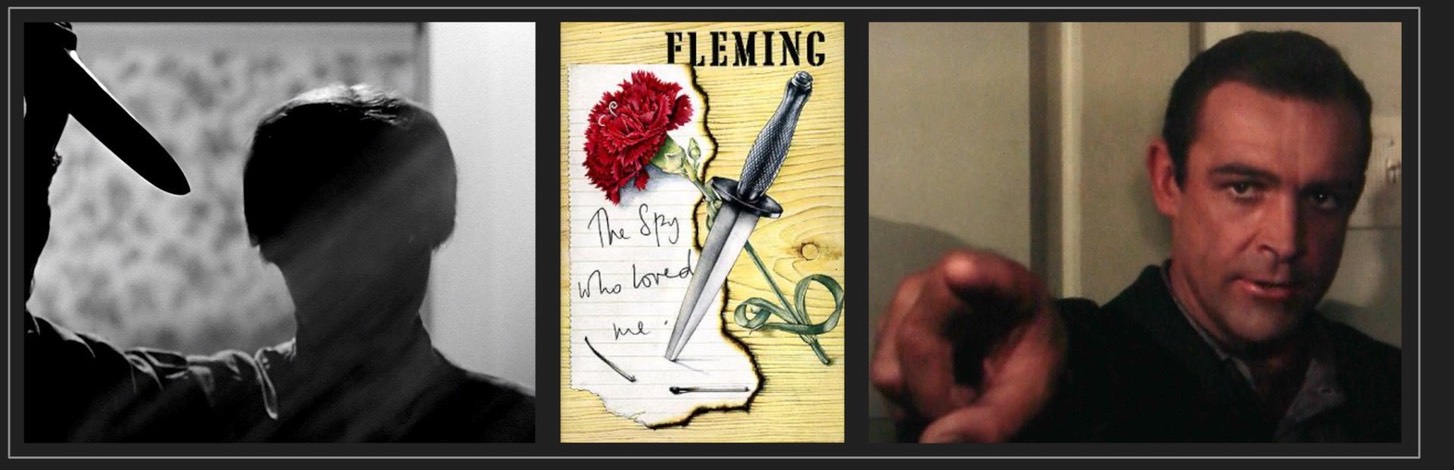

Hitchcock’s Psycho and Marnie and Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me are united by some common threads.

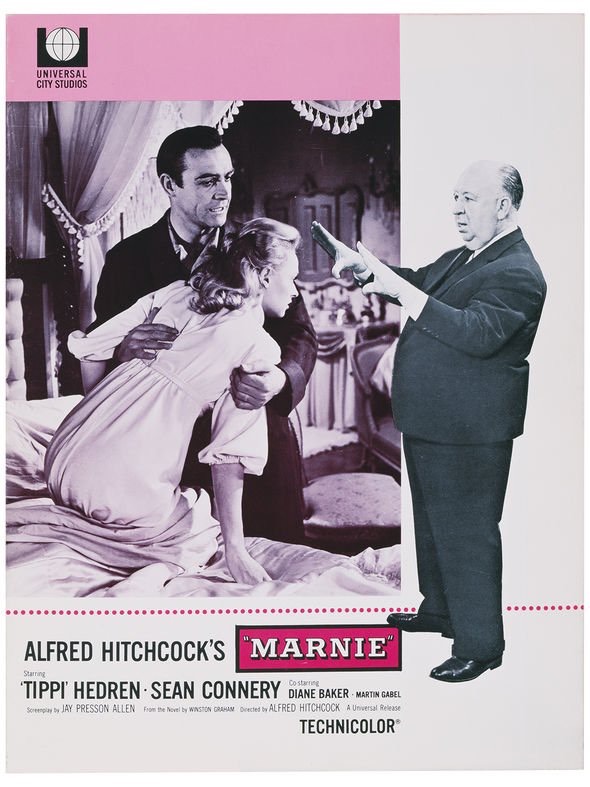

Hitchcock’s countermove was to borrow the star of the Bond series for Marnie, his follow-up to The Birds. It seemed to be a win all around. Not only did the prestigious casting placate Connery who was feeling trapped in the Bond series, but Hitchcock got a cheaper substitute for Cary Grant, one who wouldn’t overshadow Tippi Hedren, the young leading lady the director was grooming.

In Marnie’s most controversial scene, Connery’s Mark Rutland forces himself on the almost-catatonic heroine while the pair are on their honeymoon cruise, leading to her attempted suicide. Eon seemed to test the limits of rogue masculinity almost immediately with a move that smacks of one-upmanship.

Later theat same year when Connery’s Bond pressed his body and his lips against an uncooperative Pussy Galore on Goldfinger’s Kentucky stud farm, the scene was played for comedy. Audiences roared with delight, and James Bond was on course to become the infamous playboy predator of Thunderball.

If Fleming himself kept a close an eye on anyone in the movie business besides Disney, it may have been Alfred Hitchcock, whose suspense films had often involved espionage, counterspies, and implicit sexual themes. Hitchcock’s Psycho, based on Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel, could have been a roadmap for Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me, written a year after the Hitchcock movie premiered.

Bond:

The other looks like the worst kind of psycho.

If From Russia, With Love is largely a clever adaptation of Disney-princess movies, then could The Spy Who Loved Me be a twist on Hitchcock’s Psycho? Perhaps, especially since the title is a word James Bond uses to describe one of the thugs in Spy, and it's the only time he says it in any of the Bond novels. If we imagine Fleming’s book as a parody with an extended prologue, then even the long backstory in Spy could be a nod to the famously unconventional structure of Psycho.

Hitchcock sets up audience expectations by taking his time to establish Marion Crane’s romantic and economic predicaments, before pulling the bathroom rug out from under everyone at the Bates Motel. Fleming goes much further, spending half of his novel relating the life story of Vivienne Michel, from early childhood until the moment when her supercharged Vespa pulls into the Dreamy Pines Motor Court, where a nightmare scenario awaits.

Instead of meeting a lone psychopath fixated on his dead mother, Vivienne runs into an assortment of sketchy characters including two sadistic hoodlums. In both Psycho and The Spy Who Loved Me a young woman is menaced in a creepy motel, there’s a disturbing scene involving the young lady in a shower, a car is submerged in a nearby body of water, and at the last minute an authority-figure steps forward to explain everything.

The chief difference between the two works, besides critical and audience reception, is the timely entrance of James Bond in the Fleming novel (although in a coincidence of casting, Marion Crane’s boyfriend is played by John Gavin, later recruited for the role of Bond in Diamonds Are Forever, though never called up for active duty).

Bond’s unseen finger on the buzzer in The Spy Who Loved Me is a pivot-point, equivalent to the arrival of the shadowy figure we see slipping into Ms. Crane’s motel bathroom in Psycho. Both stories are not only about to take dizzying turns, but swap genres. Psycho, which begins as a seedy crime thriller, suddenly turns into a horror film; The Spy Who Loved Me is horror that shifts gears at the buzzer to become a James Bond thriller.

Key ingredients of Psycho, a female thief on the run and childhood trauma explored through psychoanalysis, are mirrored in Winston Graham's Marnie, published in 1961 and turned into a film by Alfred Hitchcock in 1964. Is there any chance that both Fleming and Graham were influenced by reading the Robert Bloch novel or by seeing the Hitchcock film of Psycho?

Let’s just say that they were all breathing the same air at the same moment. Inhaling the zeitgeist of the early 60’s, Hitchcock, screenwriter Joseph Stefano and composer Bernard Herrmann turned Bloch’s novel into a tingly horror sensation that had audiences shrieking.

Hitchcock and Herrmann, along with screenwriter Jay Presson Allen, went for something deeper and perhaps more deeply disturbing in Marnie. There are moments in the film when we have to agree with the title character that Mark Rutland could have more serious problems than she does.

While it seems doubtful that Fleming knew much about the plot of Marnie while writing The Spy Who Loved Me (Marnie was published the same year Fleming wrote his story), it’s interesting that both books are first-person narratives written by a man, but told from the point of view of a young woman.

Fleming seemed to respond to the spirit of the age by playing with some of the same raw materials as Graham and Bloch. Vivienne Michel may be the one in danger when she's menaced by hardened thugs, but it’s James Bond who’s haunted by doubt and regret, pouring out his own backstory to Vivienne (possibly divulging state secrets in the process) as if she were his analyst.

Threatened repeatedly with rape by the goons at the Dreamy Pines, it’s only after she’s been rescued, that Vivienne endures something she dubs “semi-rape.” All women love it, the heroine explains. It's a troubling turn that could have been inspired by Marnie.

Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me has something else in common with Hitchcock’s Marnie.

Both flopped with fans.