East by Southeast

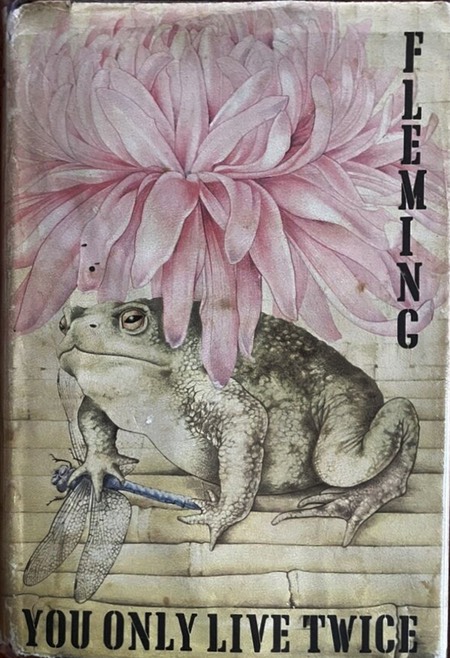

The Path to "You Only Live Twice”

You Only Live Twice is one of those movies that I can watch any time, and even if I catch it somewhere in the middle, I will probably stay until the end. It is one of a handful of films that delivers an actual jolt of nostalgia for me.

Not that it takes me back to my own childhood or what seemed to be a simpler era. It’s simply the early Bond saga’s well-earned valedictory lap.

Plus it’s a movie that just works. Each scene fires on all cylinders and whisks us along to the next one. Its breezy pace made film critic Pauline Kael dub director Lewis Gilbert “an efficient traffic manager,” and while she’s not wrong, much of the credit should go to screenwriter Roald Dahl and editor Peter Hunt (taking over for Thelma Connell, whose three-hour cut was considered tiresome) and an ensemble of actors who knew what sort of film they were in.

Additional credit should also go to Alfred Hitchcock, whose North By Northwest added the secret sauce to the spy genre: the great action scene that’s so expertly assembled that it packs a kick even if it makes no sense whatsoever. The celebrated crop duster scene may be particularly effective because it makes no sense. The audience can’t predict what will happen next, when it seems that absolutely anything might happen.

Hitchcock’s crop duster sequence definitely inspired Bond’s encounter with a grenade-spewing helicopter in From Russia With Love. Without it, the 1963 film would hew closer to the standard espionage thriller of the era. The helicopter attack and the scene in which a whole flotilla of boats is trapped in a wall of flames, boost the energy level late in the film, despite the fact that, as critic Stanley Kauffman’s complained, it seemed to end a few times before it finally ended.

Death by gold paint already sounds like a means of homicide that Hitchcock might have cooked up or wished he had, but it’s a case where a death that’s merely reported to James Bond in the book, becomes the on-screen starting pistol for the film, as well as the centerpiece of the ad campaign. After the success of From Russia With Love, filmmakers quickly began amplifying the more outrageous elements of the books at every opportunity.

To take another example from Fleming’s Goldfinger: The one gangster who opts out of the Fort Knox heist takes a fatal tumble down a stairwell, a death evidently deemed much too prosaic for a Bond film. While much of the movie’s charm is its pervasive nuttiness, crushing Mr. Solo together with his gold bars and a Lincoln Continental does seem a weirdly roundabout way to accomplish a very simple goal. However, it was hard to argue with the box office gold rush that ensued when the film reached theaters.

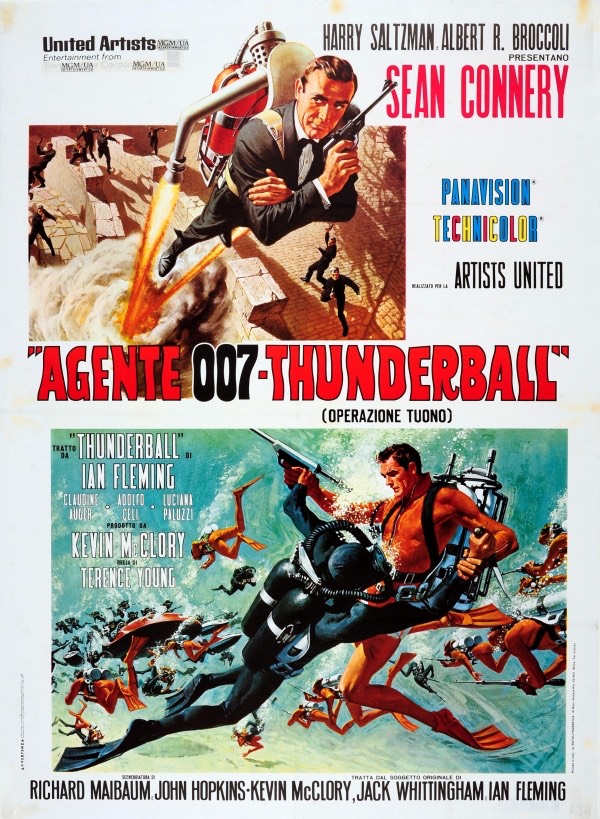

Oddball flights of fancy take wing right off the bat in the film version of Thunderball. No more grappling hooks for Bond, who apparently enters and exits a chateau by scaling the wall with a Bell Jet Belt. By the time he straps on the aquatic equivalent while muttering “And the kitchen sink” for the climactic undersea battle, any shred of realism has long been abandoned in favor of high-tech hijinks.

Judging from the all time high ticket sales, audiences evidently found the trade-off more than satisfactory.

The fifth film with Connery in the role of Bond, You Only Live Twice, was given full rein to concoct its own plot, so long as the result was seasoned with locales and just enough names and bits of business from Fleming’s novel that it could be considered an adaptation. Thus it became the first Bond movie to establish a basic formula: assemble a program of audacious, loosely interrelated scenes that keep the story moving forward until Bond finds the correct button to press or to prevent someone else from pressing.

The bustling pace of You Only Live Twice works in tandem with the “crop duster” effect, which comes into play in many of the big action scenes, giving the audience little time to reflect on whether anything they’re watching makes a whit of sense. In fact, the death of Henderson, which really gets the ball rolling, seems to have been staged as a salute to the murder of the U. N. diplomat who dies in Cary Grant’s arms with a knife sticking out of his back in North By Northwest. That movie made no sense, and it was delightful.

After Henderson’s death there is a brief fight between Bond and the killer, which leads to a brilliantly-staged sequence in the Osato Chemicals building, then a high-tech bit of safecracking, followed by a running gunfight, a brief chase, and Bond’s fall through an oubliette that deposits him neatly and only slightly stirred, in Tiger Tanaka’s office.

Between the time Henderson dies and Bond drops in on Tiger, we hear one quip from Bond and a brief exchange of dialogue between Bond and a female Japanese agent named Aki. Otherwise the whole extended sequence is a visual Rube Goldberg contraption with each surprise triggering the next. Even though no single part is grounded in reality we accept them all because we’ve witnessed the chain of causation every step along the way.

Freed of any plot constraints imposed by the novel, You Only Live Twice became the prototypical Bond movie, a synthesis of Fleming and Hitchcock, with Hitchcock taking the upper berth.

Everyone on the team seemed to sense that this movie would be the last of its kind. Money was spent freely but wisely. Ken Adam had a million dollars to build Blofeld’s volcanic lair. David Lean’s frequent collaborator Freddie Francis lit it using nearly every available lamp in London and designed the overall super-saturated Technicolor palette for the film.

John Barry’s title theme, dubbed “instant nostalgia” by the composer, is a bittersweet lament which seems to acknowledge that, while this film marked the end of the road, there would be an afterlife.

Cinderella Story

A Case of Mistaken Identity

A few years back I made a YouTube video about From Russia, With Love, characterizing it as a bleak, cold-war version of "Sleeping Beauty" for a modern age.

Unfortunately I had never seen Disney’s 1950 Cinderella, and thus had no idea Fleming was riffing on that other animated fairy tale throughout most of his book, until the dragon finally showed his fangs.

The plot of Cinderella boils down to this: An orphan girl tries to get into the Palace wearing something becoming, so that a handsome prince will fall in love with her. That’s it in a nutshell.

The mission is accomplished with remarkable ease in From Russia, With Love, when Tatiana Romanova slips into Bond’s bed at the Kristal Palas wearing Cinderella’s signature black velvet choker, and nothing else.

In addition, the laundry list of story elements which Fleming obviously lifted from the 1950 Disney film would include the following:

An ominous maternal figure violates a an orphan girl's personal space

Good guys spy on the opposition through a mouse hole in the woodwork

Jealous girls in love with the same beau engage in a clothing-ripping tussle

A faithful friend has bloodshot, watery eyes and a talented nose

An evil, skulking villain is chased out a window and falls to a cobbled street

The story makes a sharp turn on the Orient Express where it does become Sleeping Beauty. Fortunately, the wizards at “Q” Branch have equipped Bond with a dragon-slaying sword that pops into his hand as if by magic.

If anyone objects that the weapon is really only a dagger and that Bond also pumps a few bullets into Grant, I always point out that the blade is from “Wilkinsons, the sword makers,” and Fleming goes to some lengths to convince us that the wound it inflicts is indeed lethal. The bullets only let Bond put down the dying beast before those “violet teeth” can reach his tender flesh.

What I really should have said from the beginning is that From Russia, With Love is the story of a girl who keeps hoping she’s in a Cinderella story, until shortly before the chloral hydrate kicks in. If not for Bond, she just might sleep forever.

OHMSS / Book v Film

The Hour of the Gun

Before 2006, the 1969 film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service seemed the closest moviegoers might ever come to seeing a faithful cinematic adaptation of one of Fleming’s James Bond thrillers.

From Russia With Love seldom veered too far off-course, despite the unnecessary complication of having Rosa Klebb report to Ernst Stavro Blofeld instead of her former bosses at the Kremlin. The film also ends on a sprightly note, unlike the book which concludes with Bond collapsing to the floor as his vital signs fade.

At least the movie version permits Bond to be imperiled by Rosa Klebb’s poisoned shoe-blade, only to be saved at the last second by a timely shot fired by Tatiana. It was an ending which the filmmakers surely borrowed from Fleming’s Thunderball, and would reuse when it came time to film that book.

Fleming’s Bond was not invincible and occasionally did need rescuing. Alas, some of his confederates seemed to pay the toll for Bond’s unlikely escapes. Felix Leiter loses parts of himself in Live and Let Die, Kerim Bey dies on the Orient Express in From Russia, With Love, Quarrel is immolated by dragon-fire in Dr. No, while neither of the Masterton girls lives long enough to witness the final chapter of Goldfinger.

Goldfinger, the breakout hit of the series, quickly became the glittering gold-standard of Bond films. The producers came to believe, somewhat superstitiously, that at minimum one young lady needed to be offered up as a sacrifice during the story, though dispatching two would be ideal.

Thus in the film version of Thunderball two women are marked for death, Bond’s ally Paula, and SPECTRE assassin Fiona Volpe. When it came time to write the screenplay for You Only Live Twice, Roald Dahl dutifully penned a touching death scene for Aki (who ingests a dose of poison meant for Bond), and then arranged for a school of piranha to feast on the devious Helga Brandt.

Like the plot itself, these characters had to be invented for You Only Live Twice, since a strict translation of Fleming’s book would have made no sense, the work having been conceived by Fleming as a sequel to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

With the cooperation of the Alpine snow season in 1969, O.H.M.S.S. was adapted rather faithfully for the screen that year, although a few significant events had to be restructured, and Bond was permitted to be naughtier in the film than he was allowed to be in the book.

In the film, Bond treats Tracy rather roughly at the start of their relationship (even if she did pull a gun on him first), and he seems determined to sleep with any number of the young ladies cooped up in Blofeld’s dormitory. Amusingly, the surname of his first conquest has been changed from “Windsor" to “Bartlett," perhaps to avoid offending the British Royal Family.

In the book, details of Blofeld’s scheme must be pieced together from clues Bond provides when he makes his way back to London. In the film, Blofeld has confidently spilled the beans out loud before Bond escapes. The timing of that escape has also been shifted slightly during its transfer to the screen. In the book our hero hightails it while an associate is being tortured to extract information which would surely put Bond in peril. In the film, however, Bond’s cover has already been blown when he begins his breakneck descent from Piz Gloria on a pair of stolen skis, and his only confedeerate on the mountain has already been exterminated.

Although Tracy helps Bond elude Blofeld’s henchmen in the book, she is not captured during their pursuit. Therefore the later assault on Piz Gloria is not a rescue mission, as it is in the film, but merely another round in the high-stakes match between Bond and Blofeld.

The wedding of James Bond and Teresa di Vicenzo, a suitably lavish affair staged at the Draco estate in Portugal in the film, is a simple ceremony performed at a the Munich consulate in Fleming’s novel. But potentially the most significant detail from the book omitted from the film is the tidbit Bond receives about a phone call placed to the consulate by a German woman claiming to be a reporter, who inquires about the timing of the happy event.

The book sometimes casts an unflattering light on James Bond in its depiction of him as a latter-day Gawain, a knight who fails to live up to a code of honor. Besides risking a roll in the hay with one of the young ladies under his host’s supervision, Bond skedaddles, leaving a comrade to be tortured to death. He asks Tracy to marry him just before setting off for another inning of the dangerous game with his enemy, and immediately after the wedding ignores a suspicious call which should set off alarm bells.

For those aware of the book’s debt to Middle-English literature, Fleming provides a ticking clock as the newlyweds ride away after their thrifty nuptials. Glancing at his watch Bond notes the time as 11:45. Readers are informed that more than ten minutes have elapsed when the Maserati, which had appeared behind them as a distant red dot, suddenly begins to make its move.

It may have been the exact timing of the Green Knight’s return-blow on New Year’s Day in the Middle-English poem, that gave Fleming the idea of merging Sir Gawain and the Green Knight with an episode of a TV Western, one featuring a famous lawman who decides to hang up his guns for good and settle down with a beautiful but troubled young lady named Teresa. She was doomed, of course, as was almost any frontier lass who agreed to tie the knot with the leading man in a Western series.

It must have struck Fleming as more appropriate to end his modern take on the story of a failed Arthurian knight, not with the swing of a blade, but a flash of gunsmoke at high noon.

Pat Garrett holds his slain Teresa in “Bitter Ashes,” an episode of The Tall Man which aired months before Fleming wrote a similar scene for OHMSS

James Bond, Therapist

Cinema Sins for 100, Alex

My first encounter with a Bond film in a movie theater was seeing Alfred Hitchcock’s Marnie in 1964. I was either 13 or would soon turn 13. I knew there was such a thing as a Bond film, had read Fleming’s Goldfinger and had seen a photo spread of publicity stills for From Russia With Love in a popular magazine (probably Look).

While I technically knew the difference between a Hitchcock film and a Bond film, after finally seeing my first genuine Bond film I couldn’t shake the sense that I had already seen one.

Sean Connery seemed just as stylishly dressed and immaculately groomed in Marnie as he would be several months later in Goldfinger, and really did seem to be playing approximately the same role twice.

He is on the trail of puzzling cases in both films, and plays games with his chief opponents. In both, he works out of a home base which includes a patriarchal figure, a flirtatious female, and an expert with whom he maintains a contentious relationship. “M,” Moneypenny and “Q” from Goldfinger are neatly balanced by Mr. Rutland (Alan Napier), sister-in-law Lil (Diane Baker), and banker “Cousin Bob” (Bob Sweeney) in Marnie.

And, oh yes, Connery plays a man who indulges in nonconsensual intimacy in both films.

According to screenwriter Jay Presson Alan, the controversial and truly disturbing marital assault which occurs in Marnie was the main attraction for Hitchcock, perhaps his sole reason for wanting to direct the film. When the project’s first scribe, Evan Hunter, tried to eliminate the problematic scene altogether, he was promptly sacked and replaced with Ms. Alan.

After screening prints of Dr. No and From Russia With Love, Hitchcock and Alan agreed on casting Sean Connery to play the man who blackmails a frigid, compulsive thief (Tippi Hedren) into marrying him. Connery’s solidifying identification with 007 was played up in studio press releases concerning the actor’s addition to the cast of Marnie.

The Master of Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, announced he's getting together with the master of counter spies, James Bond-or at least with the man who plays Bond on the screen, Scotland's Sean Connery…

Hitchcock said he was going to present a new Connery—instead of being the much pursued bachelor, he'll play an understanding husband. 'It will be a real switch,' a Hitchcock representative explained after the announcement. 'He may not shoot anybody through the whole picture.'

Despite what the announcement claimed, the chief discernible difference between the Connery of the Bond saga and the one in Hitchcock’s Marnie is a matter of perhaps a millimeter of visible eyebrows.

It seems that Hitchcock deliberately cast the man known for the role of James Bond as the ultra-masculine predator in Marnie, to underline the darker side of cinema’s newest hero.

However, the director couldn’t resist lightening the mood with a sight gag, panning the camera away during Mark’s savage assault to frame a shot of the porthole in the couple’s cabin. It’s a disquieting callback to the final scene of North by Northwest, where the train carrying a honeymooning couple roars into a tunnel. Are viewers supposed to chuckle when they see the porthole or merely be relieved at the opportunity to look away?

Hitchcock also takes some of the edge off Marnie’s suicide attempt the following morning by giving a resuscitated Tippi Hedren the best quip in the film. When Connery asks why she tried to drown herself in the pool instead of jumping over the side of the ship, she replies, “The idea was to kill myself, not feed the damn fish.” Again there’s a chuckle, but perhaps a nervous one.

After completing his final scene on Marnie, Connery enjoyed a brief celebration with the cast and crew before rushing off to join the production team on the set of Goldfinger, his fourth film in the past twelve months.

Connery’s character would soon have to force himself on the struggling body of another attractive young woman as she futilely tries to fight off his carnal advances.

Since no such scene exists in Fleming’s novel, I’m tempted to wonder if the tussle in Goldfinger’s barn with Honor Blackman as Pussy Galore, was suggested by its disturbing counterpart in Marnie. Though Ms. Galore protests that she’s “strictly the outdoor type,” as soon as Connery’s lips press down on hers, Blackman’s struggling arms suddenly encircle his shoulders and she practically inhales him.

When John Barry’s playful underscore for the scene builds to a romantic swell, as if the film had suddenly turned into a parody of From Here to Eternity, audiences guffawed. It was not only a perfect embodiment of egotistical male fantasy, but a logical extension of the film’s fairytale milieu.

The mischievous imp’s golden spell was broken, not with a kiss, but a roll in the hay.

Unfortunately, the lesson learned by the production team was that audiences would let Connery’s Bond get away with anything.

The Notorious Mr. Bond

Learning from the Master

A few years ago I heard a pair of YouTube creators agree that Fleming’s From Russia, With Love was largely a retread of Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Unless I misunderstood the conversation, I’m forced to conclude that both reviewers were unaware that Fleming’s book was published two years before the Hitchcock film arrived in theaters. In fact, it was published even before Hitchcock’s collaborator Ernest Lehman had finished writing his screenplay, which was a wholly original work.

On the other hand, I do believe they were correct about Fleming taking his cue from an Alfred Hitchcock film, not North by Northwest, however, but a much earlier production. The 1946 espionage thriller Notorious uses the same basic ploy as Fleming’s novel - dangling a beautiful recruit as bait to snare an enemy agent.

In Notorious, American operative T. R. Devlin (Cary Grant), convinces Ingrid Bergman’s Alicia Huberman to infiltrate a group of Nazi sympathizers who've fled to Rio. Devlin, despite having fallen in love with Alicia, reluctantly suggests that she become intimate with one of the group’s leaders, Alexander Sebastian (Claude Rains), a move which will give her access to a vital secret hidden in his wine cellar. Alicia not only climbs into bed with Sebastian, but decides to marry him. When Sebastian discovers evidence that his new bride is a spy, he and his mother begin administering just enough poison to keep Alicia incapacitated as her life slowly ebbs.

Besides borrowing the racy plot (while inverting it so that the villains steer the femme fatale into the hero’s bed), Fleming also adopted Hitchcock’s use of a MacGuffin, defined by the director as an object which all of the characters are intensely interested in, while the audience is not. In Notorious the MacGuffin is a wine bottle filled with granules of radioactive pitchblende. In From Russia, With Love it’s a Specktor decoding device, much coveted by MI6, but rigged to explode when examined.

From Russia, With Love is the box of Crackerjacks of Bond novels, with a succession of prizes tumbling out in every chapter. Mixed in among the fairytales and Disney references are sly salutes to the thriller-writers of Fleming’s youth, beginning with a mention of P. G. Wodehouse on the very first page of text. Bond’s nom de voyage is “Somerset.” Red Grant cautions him against trying any “Bulldog Drummond stuff.” The Third Man is called out repeatedly, while an Eric Ambler paperback reinforces Bond’s cigarette case in hopes of making it bulletproof.

Did Alfred Hitchcock also make the cut - if not by name, then with one of Fleming’s custom-made calling cards, a sort of i.o.u. for borrowing someone else's plot device? It’s just possible that Fleming did slyly acknowledge a small debt to “the Master of Suspense.”

A quick accounting of Fleming’s vocabulary shows that he seldom employed the word “notorious” in his writings, only once or twice in the earlier books which I sorted through, for a total of perhaps three occurrences total in all of his novels prior to From Russia, With Love.

In this novel alone he uses the word “notorious” three times. Of course it could be mere coincidence. But, no, twice would be coincidence.

It also may be no coincidence that Hitchcock returned the honor by making the hapless protagonist of his very next film (Cary Grant again) make a long journey on a westbound train in the midst of a nest of spies, including a seductive young woman whose allegiance is questionable.

Shortly after From Russia, With Love rolled off the presses to a generally warm reception, rumors were floated about the possibility of a film version directed by Hitchcock and starring Cary Grant and Grace Kelly, teaming up to recapture the box office allure of To Catch a Thief. When the director’s latest film, Vertigo, was met with hostile notices and audience disinterest, the rumor mill quickly went dry on the subject of Mr. Hitchcock’s involvement in a Bond film.

A few years later the cross-pollination between Fleming and Hitchcock would bleed over into the Eon film series, with the production team lifting the crop-duster scene from North By Northwest to add some fireworks to the movie adaptation of Fleming’s novel.

Not only would Hitchcock’s return volley be bold, but it would ultimately alter the public’s perception of James Bond for decades to come.

Following Up

Shades of Difference

I was excited to learn that Timothy Dalton was in contention to play James Bond when Roger Moore turned in the tux after A View to a Kill in 1985. Although seeing him as a swashbuckling character named Prince Barin in the 1980 Flash Gordon got me to musing about Dalton as Bond, he had probably been percolating in the back of my mind for a while.

Having observed Dalton as the bitchy Philip II of France in The Lion in Winter, the obsessively driven Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, and most recently as a stern yet surprisingly playful Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre, I thought it might be refreshing to see an actor with some range essaying the role of Bond, even if Roger Moore’s successful tenure had proven that range was not exactly a prerequisite for the job.

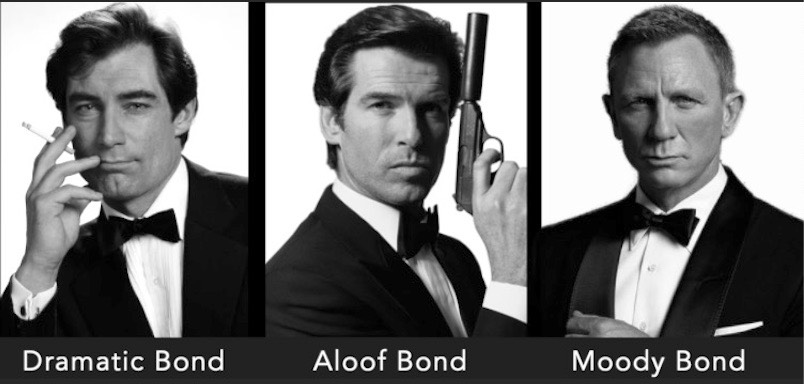

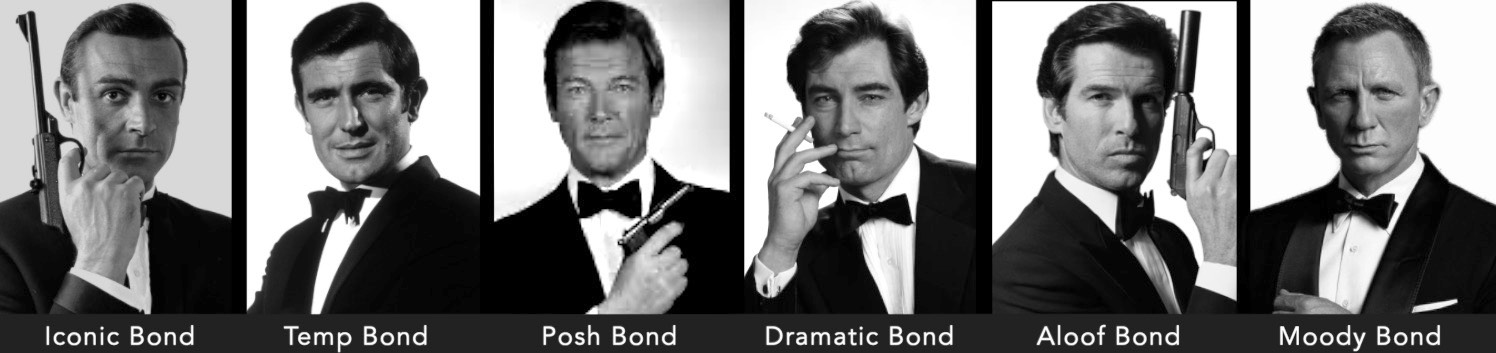

There is in fact a real kick to watching Dalton register giddy delight during a spin on a ferris wheel or witnessing the furtive energy of a vengeful 007 champing at the bit to settle a score. The Walther in Dalton’s hand looked as if it might go off at any moment on its own. Along with a different Bond there was an accompanying change in the nature of the stories being told. Improbable flights of fancy such as undersea empires and laser battles in low-earth orbit, had been scaled back to the more firmly-grounded hazards of drug cartels and desert insurgencies. Alas, the new adventures could also feel a bit commonplace and generic, less like a job for MI6 than Seal Team Six.

Dalton had almost lost the role of Bond to Pierce Brosnan, who would have been cast in The Living Daylights if not for an abrupt change in the status of his TV series Remington Steele, where he played a fake private detective equipped with James Bond’s wardrobe and sense of joie de vivre. During a prolonged lull between productions Dalton returned to his first love, the legitimate stage, Brosnan stepped in front of the gun barrel.

Remarkably, Pierce Brosnan would become the third actor to win the coveted role of Ian Fleming’s master spy after impersonating Bond on the small screen. Roger Moore had played 007 in a comedy sketch on the variety show Mainly Millicent in 1964, while George Lazenby’s entrée into show business consisted of dressing up to resemble Sean Connery’s Bond for a series of TV commercials. Besides casually auditioning for the role during the entire run of Remington Steele, Pierce Brosnan was for a few years afterwards the focus of a series of Diet Coke ads which played up the actor’s suave aplomb in the face of mortal danger.

As Bond, Brosnan came across as a blend of Moore and Dalton, the cool charm of Moore but spiced with a dash of Dalton’s vigor. According to legend, Roger Moore had insisted on a stipulation in his contract that he would not be required to run. Brosnan was the diametrical opposite, whose contract seemed to require him to run like a racehorse whenever possible. Not as theatrical nor mercurial as Dalton, he was the master of the slow, steely-eyed burn, which added an element of danger to his soft Irish purr.

The filmmakers seemed to channel pent-up energy into the first movie for each new iteration of Bond before easing up on the gas pedal to coast for a while. Brosnan’s Goldeneye may have been a high-water mark for Bond movies since O.H.M.S.S., but a marked decline had set in by the time I got around to seeing The World Is Not Enough, which was certainly nowhere near enough to bring me back for more.

Fortunately, acquiring the rights to Fleming’s Casino Royale would get creative juices flowing again. The next actor to portray Bond would bear little resemblance to the men who had come before. He would be shorter, fairer, more nondescript, looking less like a model who had been selected for his ability to look darkly threatening while brandishing a gun on the movie poster, and more like the blunt instrument of Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Getting Underway

The Matter of Succession

In a recent post I took an inventory of the men who’ve been cast as James Bond thus far in the seemingly-inexhaustible film series. This was a cursory summation at best. I did not refresh my memory by rewatching everything, or by catching up with some entries for the very first time on streaming services. Rather, it is my recollection of how the various entrants struck me at the time while sitting in a theater seat with an inexpensive box of popcorn cradled in my arm.

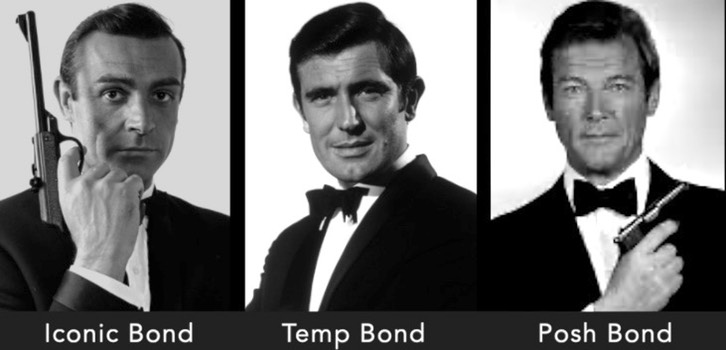

Back when moviegoing was still cheap entertainment I watched most of the Connery series, starting with Goldfinger, sometimes, several times each. After a delay of almost a full decade I finally got a look at the first two entries in the series at a drive-in, a few months before the premiere of Diamonds Are Forever. Thus, while some segment of the population considered Sean Connery irreplaceable, I had only seen him in three Bond films before George Lazenby stepped in.

In fact, the Bond movie which garnered the most repeat viewings from me upon its initial release was On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the one which had also been buffed to highest sheen of technical accomplishment thus far. What’s clear in retrospect is that the company should have used the previous star’s departure as an opportunity to reboot. Instead they seemed bent on trying to gaslight the audience.

A model whose specialty had been dressing as James Bond for a series of commercials, and who only turned 30 after filming wrapped, George Lazenby shows promise in O.H.M.S.S. He is entirely believable as a raw recruit being handed his first assignment, but perhaps not as a living legend in the spy trade.

“This never happened to the other fella,” Lazenby laments during the pre-title sequence. The title montage includes snippets from earlier entries in the series. During playful office banter with the new 007, Moneypenny squeals, “Same old James - only more so!” Bond daydreams at his desk while rummaging through souvenirs of past missions as the soundtrack plays familiar John Barry cues from previous films.

It’s as if the filmmakers decided to force the audience to watch a heavy-handed treatise on the concept of recasting a part, before the movie quite gets going.

Lazenby isn't terrible in the part. He’s just a freshly-minted novice who’s trying to avoid tripping over the cables. In that respect he’s a bit like the Connery of 1958’s Another Time, Another Place. Appearing as Lana Turner’s doomed love-interest, the freshman leading-man had been given pages of lines to recite but no real character to play. By rights the role should have gone to Roger Moore.

My favorite anecdote concerning O.H.M.S.S. is the one where Harry Saltzman asks an attendee at a press screening, “So what do you think of my new monster?”

“You screwed up, Harry,” the man replied. "You should have killed him and kept her.”

Any story concerning Lazenby’s departure should be taken with a grain of salt. The version which has Lazenby being pressured by his agent to turn down a lucrative multi-picture contract to keep playing Bond, in favor of making trippy counterculture flicks on shoestring budgets, may have been an invention designed to save face all around. The fact is that replacing Connery had turned out to be harder than expected. So producers lured him back with an unprecedented payday.

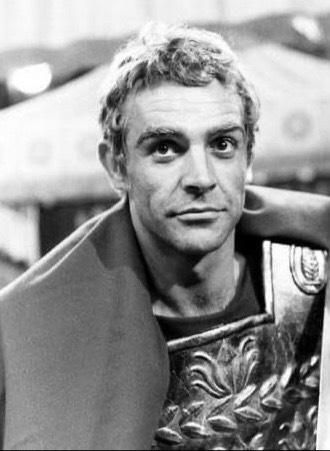

Connery’s most prestigious motion picture credit before Dr. No had been the young male lead in Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People, on the heels of playing loutish, oversexed villains in Action of the Tiger and Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure.

Watching a vintage recording of Connery as Alexander the Great in Terence Rattigan’s Adventure Story, a televised drama from 1961, gives us a glimpse of an actor clearly on the brink of stardom and looking for new worlds to conquer. He played Rattigan’s Alexander, Tolstoy’s Count Vronsky and Sharkespeare’s Macbeth within a matter of months, one year after winning the standout role of Harry Hotspur in the BBC’s An Age of Kings.

When Connery could not be convinced to stick around for a follow-uo to Diamonds Are Forever, producers decided to seek another actor with a proven track record.

After three years at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where he perfected a Mid-Atlantic accent and the art of raising either of his eyebrows or both at once, Roger Moore had gradually built up a resume of supporting roles and third-billed leads on television and in films. His career received a major boost in 1958 when he was cast in the title role of the TV series Ivanhoe, which was followed by steady work in Warner Brothers Westerns, including a short stint as Beau Maverick.

Moore scored the part of Simon Templar in the lead-up to the long-running TV series The Saint in 1962, the same year Connery starred in Dr. No. After The Saint left the airwaves in 1969 Moore teamed up with Tony Curtis as a mismatched pair of do-gooders in The Persuaders, a series which ended its short run just in time to free up Moore for Live and Let Die in 1972.

I had seen Moore as Beau Maverick, as Simon Templar, and as Tony Curtis’s urbane partner, and wasn’t looking forward to his impersonation of James Bond. I needn't have worried. If Moore could be guaranteed to turn every role he played into some slight variation on the suave, earnest, imperturbable gentleman he had perfected over a decade of mostly forgettable films, at the very least he was an actor who seemed to know what he was doing.

There was also the propulsive energy of Paul McCartney’s title song and George Martin’s accompanying score to smooth over the rough patches. Besides, Bond films had become a phenomenon less concerned with fantastical schemes to be foiled ingeniously, than with a series of zany chases punctuated by one-liners and perfectly-timed pyrotechnics.

The Man With the Golden Gun was another matter. Fleming’s book is barely an outline, a means of settling up accounts and putting Bond back into play without the weight of emotional baggage from past transgressions.

Today it’s difficult to remember what the film version is even supposed to be about. There is talk of an energy crisis and some sort of solar-powered contraption. A bounty is placed on James Bond’s head. That amusing Southern sheriff from the previous Moore film pops up for laughs. Somewhere in the proceedings a car executes a midair corkscrew maneuver accompanied by a slide-whistle sound effect, while moviegoers groan. We see a man, or perhaps two men, sporting an extra nipple each, and a gentlemanly duel gets underway on a beach. Then, for some reason, everything starts to explode while Bond dashes about with a bikini-clad girl.

The audience in my theater began trudging up the aisle before the end credits rolled and I was tempted to join them. I have seen the movie exactly once.

It had been ten years since Goldfinger took the world by storm and now the last of Fleming’s Bond thrillers had finally been committed to film, in some form or other. Somehow, it did not seem to be a milestone worth celebrating.

The Men Who Would Be Bond

An Overdue Overview

Every fan has a favorite Bond actor, usually the first one he or she first spied glaring back at the audience through the gun barrel. Some were better than others, but the fact that they all seemed to click with some segment of the audience says something about the flexibility of the role. There is room for alternate interpretations.

So far none of the actors has borne a striking similarity to a young Hoagy Carmichael, the musician whose image was stuck in the mind’s eye of Ian Fleming as he created Bond. I am old enough to have watched Carmichael act on the TV series Laramie in 1960 and watched him hawk record collections on two-minute commercials in the 1970’s, and think I understood even at the time, what Fleming was fishing for.

I remember seeing Irish actor Derrick O’Connor battling Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon 2 many years later, and understood at the time that his was the sort of face Fleming probably had in mind - decent-looking chap, but not at all striking, not especially memorable. Asked to describe him in the film I’d have said, “the thug with the Hitler haircut.” If you look up pictures of O’Connor on IMDb you’ll see him sporting a variety of hairstyles, each of which presents him in a completely different light. He was the sort of anonymously appealing bloke who could have been Bond.

After watching Daniel Craig in Layer Cake, I noticed his name cropping up on lists of possible Bonds, but personally considered him too boyish for the part, not realizing that an origin story was in the works. The last vestige of boyishness was quickly shed soon after Casino Royale.

When I saw the actor’s face on the poster for his third Bond film, Skyfall, I thought for all the world he was beginning to resemble Ben Gazzara. Craig was already venturing into his mid-forties, an age which can have a mysterious gravitational influence on a man’s face. Oddly enough, Daniel Craig was also starting to resemble Derrick O’Connor, just a bit. In retrospect, I have to think Craig was a fine choice to play James Bond.

The series had swung into action with the iconic Bond of Sean Connery, a determined young actor who had cut his teeth on such meaty roles as Shakespeare’s Harry Hotspur and Macbeth, and Tolstoy’s Count Vronsky before signing on as 007. Appearing in five Bond films over the five-year period that saw a swelling tide of Bondmania was probably a guaranteed recipe for burnout.

The seasoned veteran was replaced by a complete novice who happened to resemble his predecessor (at a distance), making George Lazenby the first Temp Bond. He is fondly remembered for nailing the final scene of his one Bond film, and might have gone on to acquit himself well in other entries, but like other members of his generation, Lazenby decided to pursue groovier interests.

Lured back by a massive payday for the first of what would turn into three encores, Sean Connery’s return to the role in Diamonds Are Forever hinted at a restoration to former glory. Unfortunately, the book had been one of Fleming’s weakest, and suddenly morphing his story about diamond smugglers into a low-rent retread of You Only Live Twice was a sure sign of series-fatigue.

The resulting garish, slapdash film gleefully chucks any remaining semblance of series continuity out the window, offering in return little besides Connery’s charm and a string of amusing stunts. Amazingly, that was enough to earn the film a temporary spot in Guinness World Records for the fastest sprint to $30 Million at the North American box office.

Roger Moore modestly admitted that he was no one’s first choice for most of the plum roles he played. His Beau Maverick filled the boots of departing James Garner’s Bret, he became The Saint after Patrick McGoohan turned down the opportunity, and though Moore played James Bond for over a decade, scripts were often slipped to Connery first in the vain hope that he would be tempted to return.

Moore’s first outing, Live and Let Die, had the advantage of being based on one of Fleming’s earliest thrillers, bypassing continuity issues. Stressing comedy and improbable set pieces, the film tiptoes through a racial minefield and tones down the more sadistic aspects of the book. It’s Bond as jolly family entertainment, if occasionally cheap-looking, an uneven film propped up by a solid score.

Roger Moore had dropped twenty pounds for his freshman effort, in which, despite being three years older than Connery, he resembles an up-and-coming male ingenue. Stiff and unconvincing in fight scenes, Moore’s Bond is an assemblage of dulcet tones, good manners, and a perfectly-tailored suit, which all worked together well enough to get by.

1983 saw a rare conjunction. All three actors who had thus far played Jame Bond appeared onscreen in various iterations of the character. Because of copyright restrictions Lazenby could only be identified as a “JB” for a cameo appearance in The Return of the Man From U.N.C.L.E. : The Fifteen Years Later Affair, but everybody knew.

Moore’s version received a box-office boost by arriving in May. For better or worse Octopussy, based on nothing in particular, threw in everything but the kitchen sink, followed by the kitchen sink. Connery’s headliner, a forced remake of Thunderball, arrived in autumn and may have won the majority of laurels handed out that year if not the receipts. Considering the fact that the character had been written as a man in his mid-thirties, all three contestants were past their sell-by date. Connery wisely played his turn as a retirement film.

Moore unwisely prolonged his tenure long enough to encompass A View to a Kill, a madcap ripoff of Goldfinger, before yielding the field to Timothy Dalton for The Living Daylights.

The only British actor who could match Connery’s glowering brow, Dalton had been eyed as a possible replacement for Connery since the late 1960’s, when he was in his early 20’s. Reportedly, he had also been approached to take over for Moore in 1983’s Octopussy, but with Connery launching a competitive film set to open the same year, Eon flinched and stuck with their proven star.

Finally cast in the part at age 40, Dalton was given a thrilling introduction which, unfortunately, remained a career highlight, although he bristles with tightly-controlled energy throughout both outings as Bond.

The Living Daylights tantalized audiences with echos of From Russia With Love, before veering off into 1980’s geopolitics. Dalton’s second outing, Licence to Kill mined unused bits of the novel Live and Let Die along with the short story “Risico,” as if to sprinkle some genuine Fleming flavoring over the proceedings. At the time the film struck some critics as little more than a violent, unpleasant big-screen incarnation of television’s Miami Vice, and charted a marked decline in revenue.

Pierce Brosnan had been tapped to replace Moore after A View to a Kill but was forced to bow out when his television contract was extended for a fifth season of Remington Steele. The show’s first four seasons had seemed to be one long audition reel promoting Brosnan as the next 007. After Timothy Dalton was cast in the role, Brosnan continued to play a Bond-lookalike in Diet Coke commercials while he bided his time. Six years younger than Dalton, he could afford to wait.

When Brosnan attended the premiere of his first Bond film, Goldeneye, he was only 42, but had spent the past eight years standing in line. While casting a man who had made a career out of impersonating James Bond sounded like a blueprint for Lazenby 2.0, the resulting film was superb, a lavish, crisply-directed spectacle headed by good actors all around. Goldeneye set a standard of excellence no subsequent Bond film would attain until Casino Royale.

The filmmakers had given Brosnan’s Bond a lady-boss and a directive to dial down the male chauvinism a notch, but otherwise to keep making money by doing more of what had worked before. The money did keep rolling in, even when creative energy seemed to dip to an all-time low.

By 2005 there was finally a legitimate reason for a new Bond movie and a major reset for the series. Eon had at last snared the rights to Fleming’s first Bond novel, Casino Royale, and named Daniel Craig its new star.

In retrospect the rebooted series seems to consist of a string of origin stories. The loss of his first great love, Vesper Lynd, becomes the open wound that turns a fledgling MI6 assassin into the Bond we all know.

After a stirring debut Craig’s Bond becomes mired in a meandering effort to manufacture a worthy substitute for the criminal syndicate SPECTRE, a move later rendered meaningless when Eon Productions also cornered the rights to the OG organization and the villain from Thunderball.

Moviegoers next delved into Bond’s boyhood trauma in Skyfall, before going on a tour of the mysterious connection between Bond and Blofeld in SPECTRE (lest that newest intellectual property go to waste). As if to hang a question mark over the future of the series, Bond thunders away in his DB5 beside a lover who seemed to be more than just the catch of the day.

When a fifth entry was announced, screenwriters who seemed determined to leave no stone unturned, latched onto the long-dormant plot of Fleming’s You Only Live Twice. This was somehow wedded not only to the heartbreaking ending of Casino Royale but to the apparent betrayal of Bond by his most recent love interest. All dangling plot strands were lovingly knitted into a tragic libretto, set to John Barry’s recurring theme of doomed love from O.H.M.S.S.

For diehard fans of both Fleming’s Bond and the movie version, the operatic ending was either slightly over the top or just about perfect. However, casual viewers may have been left feeling as if they had been sprayed with a firehose of ideas.

The film checks an impressive array of boxes from Fleming’s novel, including a suicide mission to destroy Dr. Shatterhand’s garden of death, a daughter who will grow up separated from her father, the apparent demise of 007, and a stirring tribute to Britain’s fallen hero.

Even considering a few blatant remakes, the upwards of two dozen films produced thus far surely account for nearly every notable thought Ian Fleming ever committed to paper. Yet, there will be more Bond movies. There have to be. The Bond phenomenon long ago achieved fusion status and now generates more power than it requires to sustain itself.

Judging from the latest entry, the Bond series will start over with a clean slate. Whatever that means.

YOLT / Book v. Film

Mixing Up the Order

You Only Live Twice and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service came close to being filmed in the appropriate order, if only the weather had cooperated.

Instead, Fleming’s haunting sequel to OHMSS became the capstone to the current run of Bond films starring Sean Connery, a series which had been launched with a thinly-veiled adaptation of Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Fittingly, the screenplay for the new film was pieced together by Fleming’s friend and former Disney collaborator Roald Dahl, who shared the author’s piquant sense of humor and sense of outlandish adventure.

The book’s Bond, a broken and hollowed-out figure following the death of his wife, is dispatched to Japan to borrow the world’s most advanced code-breaker. With the help of Tiger Tanaka, the head of Japan’s Secret Service, Bond passes along the translated text of an intercepted message which helps avert what might have escalated into thermonuclear war.

Now indebted to Tanaka, Bond is offered a dangerous mission to eliminate a mysterious figure known as Dr. Shatterhand, who presides over a botanical “Disneyland of death,” where young Japanese are lured with the promise of an honorable demise. Realizing that Shatterhand is really his old enemy Ernst Stavro Blofeld, Bond accepts.

While the plot had to be jettisoned, Bond having no motive as yet for seeking personal revenge on Blofeld, the film manages to salvage some of the book’s texture. Bond saving a world on the brink of war, Bond’s fall through an oubliette, a “civilized” bath, Tiger Tanaka, Kissy Suzuki, Dikko Henderson, a faux marriage, Ama diving girls, Blofeld’s volcanic lair, even Bond’s apparent death and his Japanese makeover - are all repurposed from Fleming’s text and molded around a new threat.

It almost seems that Roald Dahl decided to bookend the Bond series to date, with a more extravagant version of the first entry, Dr. No, another film in which a secretive mastermind sabotages the space program. Besides Disney’s 20,000 Leagues, the result also has glimmerings of another Jules Verne title, Master of the World, in which a half-mad genius launches his convertible airship from an extinct volcano.

A more direct influence on Dahl’s script came from a list of detailed suggestions provided by the production team, based on what had worked best in previous films, especially Goldfinger. For instance, while it was almost mandatory to sacrifice one female victim early in the story, it would be better to sacrifice two. Thus, in addition to poisoning Bond’s ally Aki, the YOLT script required Helga Brandt to be fed to a school of Piranha. Neither character appears in Fleming’s novel. Both were conjured up to die for the sake of a formula.

If women still had to be sacrificed, at least they weren’t batted around by the hero this time. Critic Pauline Kael noted that for all of the mayhem in You Only Live Twice, Connery plays a kinder, gentler Bond here, his sexual liasions actually resembling “love relationships.”

Both the book and the film seem to tip a hat to Walt Disney. Where Fleming’s previous novel, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, traces the origin of Walt’s surname, the sequel compares Blofeld’s volcanic castle to a lethal version of Disney’s Anaheim theme park. Designer Ken Adam’s staggering concept for the climax of the film actually seems to combine the hollowed-out Matterhorn, the park's encircling monorail track, and Tomorrowland’s moon rocket poised on a launch pad, to create a literal realization of Fleming’s whimsical metaphor. It’s the star of the show.

Freed from the constraints of Fleming’s plot, You Only Live Twice was the first Bond film to venture into pure, outrageous, formulaic spectacle. That it made less money than Thunderball, can be chalked up to the glut of secret-agent content in theaters and on television that year. You Only Live Twice wasn’t even the only James Bond film that opened in the spring of 1967.

For all its silly extravagance Casino Royale arrived in theaters first and probably siphoned some of the gas from the second film’s tank..

Still, Sean Connery’s supposed swan song as Bond performed well enough that it would serve as a model for two later entries in the series, The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker. Unused elements of the Fleming novel would get a much-belated transfer to the screen in No Time To Die.

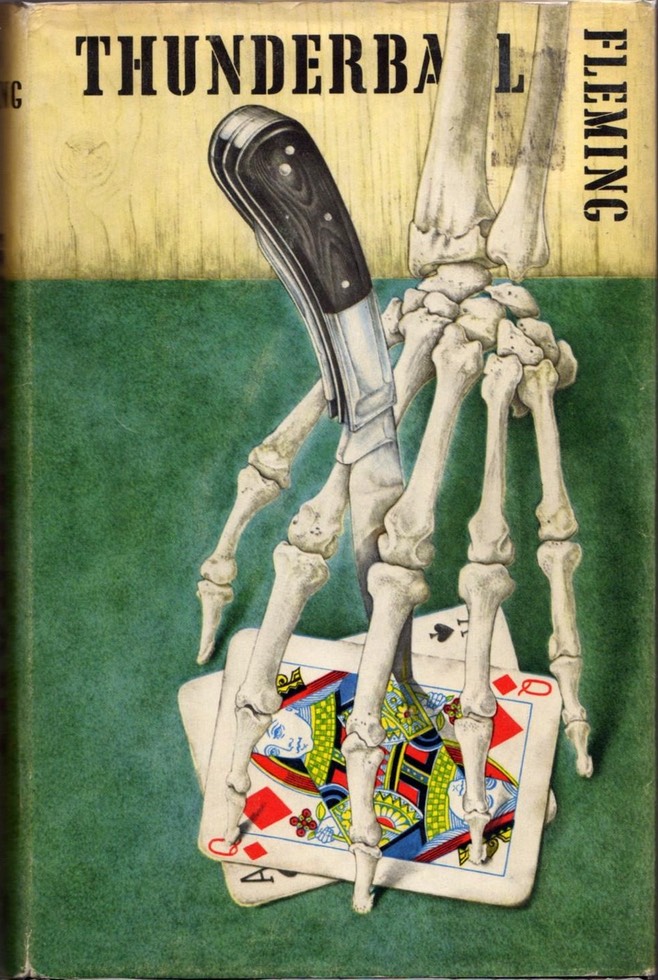

Thunderball / Book v. Film

A Bond Too Far

Comparing the movie Thunderball with Fleming’s novel is a chicken/egg proposition.

The project first took shape as a script sometimes called Longitude 78 West, an idea for a James Bond film which went through several versions sketched out by Fleming and four collaborators. Fleming’s novel is the author’s doomsday-rhapsody loosely based on the group’s abandoned screenplay. After much litigation, the original screenplay was dusted off to form the basis for two films, including the 1965 version which was called Thunderball.

I often describe each of Fleming’s Bond novels after Diamonds Are Forever as having two chief sources of inspiration which he cleverly mashes together. There may be many seasonings simmering in the pot, but the dish generally boils down to two main ingredients.

From Russia, With Love takes the threadbare plot from Charles Perrault’s tale of “Sleeping Beauty” and fleshes it out with characters and situations extracted from Disney’s Cinderella, cleverly braiding the two fairy tales together to create a brilliant story of international intrigue. Dr. No throws Rima the Bird Girl from Green Mansions into the brig of the Nautilus from Disney’s 20,000 Leagues. Goldfinger is what we might expect if the Brothers Grimm and Sigmund Freud had collaborated on a crime caper.

In that vein, I think of Fleming’s Thunderball as another rewrite of the dormant Longitude 78 West project from the late 1950’s, but a version that comes dangerously close to being a prequel to Neville Shute’s On The Beach, a grim cautionary novel about the extinction of the human race from radiation poisoning after a limited nuclear war.

The movie version is all about delivering in spades everything that audiences had lapped up in Goldfinger.

Bond’s treatment of women, or even someone who might be a woman, hits a new low in Thunderball. He belts a “widow” for opening a car door instead of waiting for a man to do it, and steals an unwelcome kiss from his nurse at a health clinic before blackmailing her into having sex with him in the steam room.

There is no assassin impersonating a widow in the book, in which Bond has what appears to be an adolescent crush on his nurse, whom he does steal a brief kiss from, but otherwise woos in an adorably old-fashioned way. Fleming may have intended Bond’s playful pursuit of Nurse Fearing to provide a contrast for his predatory seduction of Domino, culminating moments before he delivers news of her brother’s murder.

On the opening page of the novel Fleming writes of Bond, “To begin with he was ashamed of himself - a rare state of mind.” Mind you, he’s only ashamed for drinking himself into a hangover and playing cards stupidly the night before. By the end of the book, when he’s curled up on a rug next to Domino’s hospital bed like a faithful spaniel, there are more shameful qualities for him to consider.

It’s an understatement to say that Bond behaves badly in Thunderball, both in the film and the book. The difference is that he enjoys himself immensely in the film, but is so torn with guilt by the end of the book that his failings will continue to haunt him through future adventures.

A major subplot of the movie is Bond’s cat-and-mouse game with a female SPECTRE assassin who eliminates a reckless colleague in spectacular fashion and then puts 007 in her crosshairs. Bond beds the alluring assassin before swinging her into the path of a bullet meant for him. Her death is capped by one of Bond’s most pointedly sardonic quips.

An anonymous SPECTRE assassin also takes out Count Lippe in the book, but does so simply and efficiently, with no need of a high-powered rocket-firing motorbike. Besides the almost monotonous cavalcade of gadgets in the film version, a legion of casualties are throttled, gassed, poisoned, shot, blasted, skewered with spears (underwater and on land), as well as devoured by sharks.

While Thunderball is very a different book from Goldfinger, both films, one about a preposterous robbery and the other about nuclear annihilation, aim for the same spirit of giddy adventure, overstuffed with outrageous gadgets, spectacular carnage, and beautiful women.

The essence of a Bond movie had been distilled into a predictable formula which, with any luck, could be repeated with only minor modifications, to achieve predictable box office results.

Even though adhering to that formula helped turn Thunderball into the biggest Bond bonanza of them all, the moviemakers understood that they might need to dial back the sex and sadism next time.